Throughout this blog series, Playing the Long Game, we’ve underlined the importance of managing health for every patient, regardless of where they are at in their health journey. We described the potential long-term gains under this approach, as it pertains to cultural shifts, clinical alignment, and financial success. In our most recent blogs, we’ve started to explore some of the core capabilities and actions needed to power such a framework, including population health monitoring. In this blog, we’ll explore the concept of Clinical Screening. We’ll define what it is; where it fits into the broader care framework; steps needed to deploy this type of program; the capabilities required to make it go.

What is clinical screening?

Clinical screening sometimes referred to as “Clinical Identification” and “Stratification” or “ID/Strat”, is the process of identifying patients/members for proactive, targeted interventions, with the goal of improving coordination of care and avoiding unnecessary costs and utilization. In the simplest terms, it’s really about ensuring that EVERY patient receives appropriate care, at the appropriate time, with the appropriate level of resources.

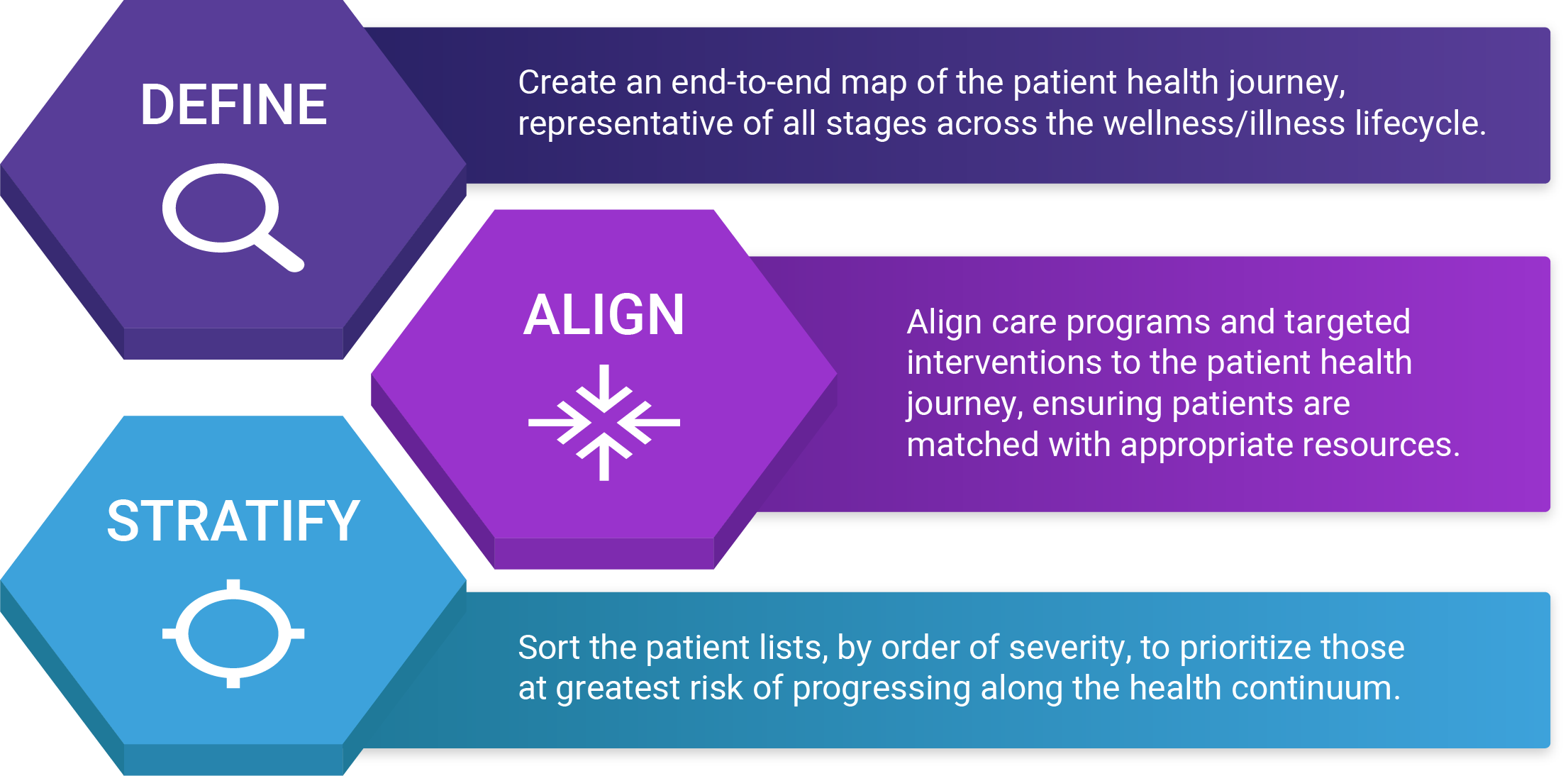

There are numerous ways to approach clinical screening, ranging from very simple to incredibly complex. Regardless of the path taken, the end result should be the same – the clinical team should have access to an actionable list of patients grouped by care/service needs and sorted based on the severity of the risk. In the following sections, we’ll break down the 3 major activities of clinical screening, which we refer to as define, align & stratify.

Step 1 Define: map the patient journey

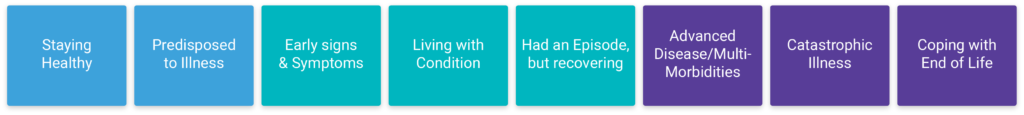

The first step is mapping the patient’s health journey. The patient health journey is a wellness/illness continuum that describes the many stages of health that a person may experience throughout life. On one end of the spectrum is a high degree of wellness and on the other end is death. Although considered to be a longitudinal map – most, if not all of us, will take detours from time to time (e.g., childbirth, injury, acute illness, etc.).

Once the phases of the health journey are constructed, the next step is to establish the criteria for defining the various stages. This can be as simple or complex as the organization wishes. It’s recommended to start small and then expand the model over time. For example, an organization could start by targeting only chronic conditions OR go really narrow and focus on a single high-risk condition.

Stages of the patient health journey

For purposes of this discussion, we’ll take the latter approach and target Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). This refers to the disease of the heart and blood vessels due to the accumulation of plaques. ASCVD can limit blood flow to the heart (coronary artery disease), leading to dangerous cardiovascular events such as heart attacks (acute myocardial infarction), as well as decreased blood flow to the brain resulting in ischemic strokes. In this section, we’ll define what each stage of the health journey would look like for someone who has or is at risk of developing ASCVD.

Healthy patients

Establishing the criteria for the “Staying Healthy” group is pretty straightforward, it includes pretty much everyone that doesn’t fall into one of the other groups. It is worth noting that under/non-utilizers can sometimes appear to fall into this group, so it’s important to keep that in mind when designing the model; there should be a way to separate the two for further analysis and triage or to use other sources of information (labs, Rx data) when the diagnosis may not indicate ASCVD or related disease.

Low-risk patients

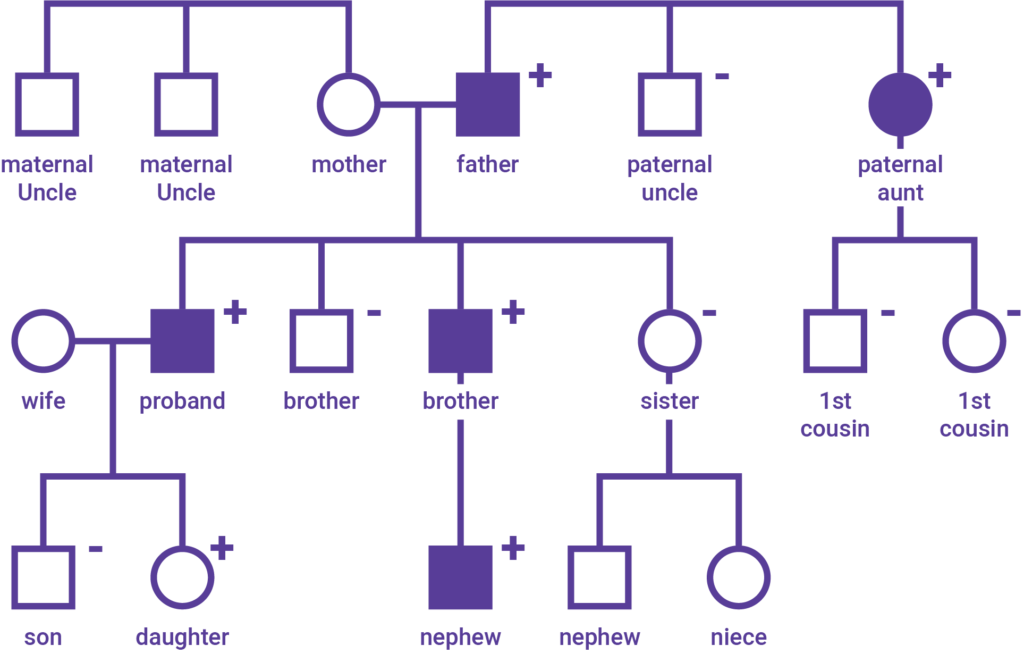

The “Predisposed to Illness” stage would include any individual who has a family history (FamHx) of disease/illness of ASCVD or related conditions, who have not yet been diagnosed themselves. This information will not be available in claims data and will most likely be found in the clinical notes section or family history table within the electronic medical record (EMR), it may also be captured external to the EMR via survey data as well.

Rising risk patients

The “Early signs & symptoms” stage would include anyone that has an indication of clinical relevance for ASCVD. This can include those with a FamHx or not. The key distinction here is that they themselves are presenting with signs. These individuals, while not yet diagnosed with ASCVD, are at greater risk of developing it. This information may be captured through Rx claims data, but labs & vital signs will also be crucial at this stage.

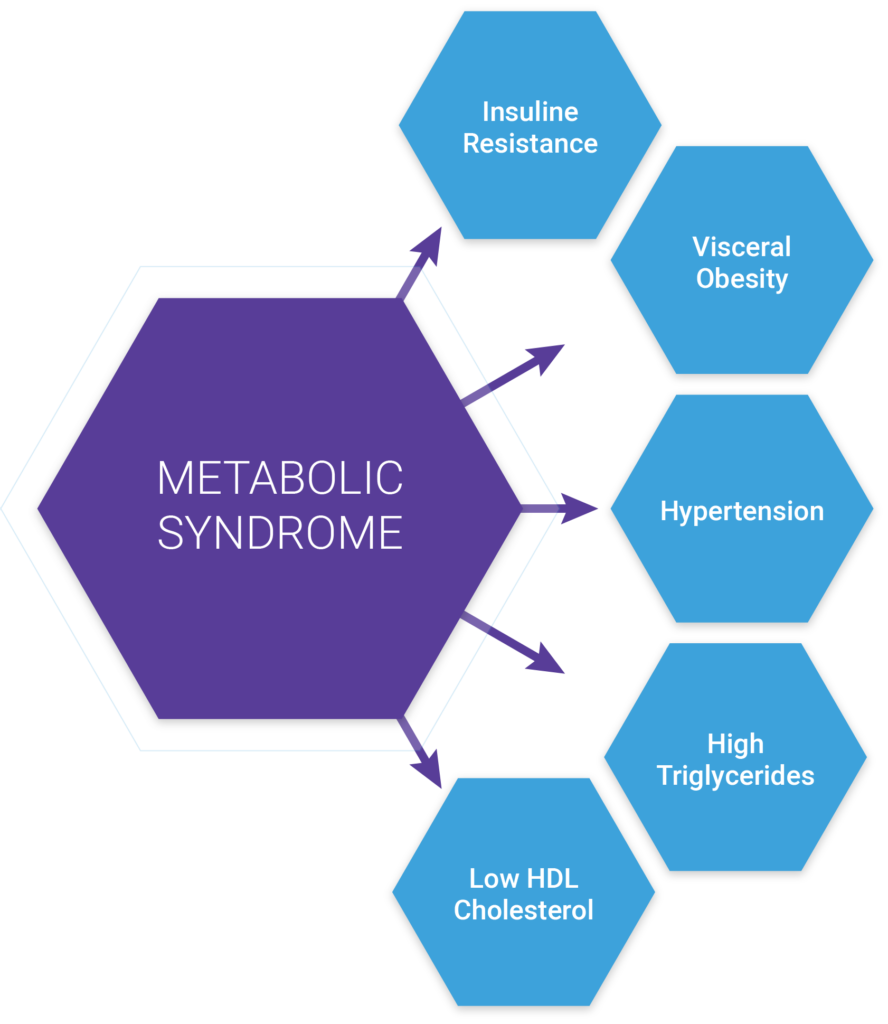

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have produced many helpful resources for identifying and treating this population early, including screening tools and treatment recommendations. An organization could also take a much less narrow approach by screening for individuals who have or are at risk of developing metabolic syndrome, which can be used to identify patients at risk for cardiovascular disease and type II diabetes. In this case, we’d look to identify patients who are presenting with three or more of the following traits:

presenting with three or more of the following traits:

- Large waist — A waistline that measures at least 35 inches (89 centimeters) for women and 40inches (102 centimeters) for men

- High triglyceride level — 150 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL), or 1.7 millimoles per liter (mmol/L), or higher of this type of fat found in blood

- Reduced “good” or HDL cholesterol — Less than 40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) in men or less than 50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) in women of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol

- Increased blood pressure — 130/85 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) or higher

- Elevated fasting blood sugar — 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or higher

There’s a great article, Diagnosis, and Management of the Metabolic Syndrome, that provides a very detailed specification on how to identify patients at risk of metabolic syndrome. This is one of many ways that an organization could approach the identification of patients.

Riskiest patients

Individuals that are in the “Living with a condition” stage, would be those that have been diagnosed with ASCVD. We would look for individuals with any principal diagnosis categories for Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI), Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), Acute Cerebrovascular Disease (i.e., stroke). We’d also look for ICD procedure codes associated with Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) or Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty (PTCA) with a look back period of at least 18 months, longer if the historical data is available.

Someone living with ASCVD maybe what we’d call “well controlled”. Although the person has been diagnosed with a disease, they are learning to live with and manage it. There are others that we’d consider not well-controlled or perhaps individuals with ASCVD with comorbidities and/or complications that should be separated and approached differently with interventions and services. Similarly, the same logic applies to those that are living with a catastrophic illness or coping with the end of life.

As you can probably already tell, the severity of one’s illness becomes a major factor in how care & resources should be deployed. This is where clinical screening algorithms and grouper models become very effective at managing risk along the health journey.

Sidebar on clinical screening algorithms & grouper models

A clinical screening algorithm is a set of rules that when applied to a dataset (e.g., claims data), allows for the consistent grouping of patients within a population by disease/condition. When building or selecting a clinical screening algorithm, there are many factors to consider, including but not limited to:

- Which diagnosis codes will be included/excluded?

- How will diagnosis codes be sourced (claims, lab values, clinical records, surveys, etc.)?

- How far back, in the patient’s history, will the algorithm look?

- How many diagnosis codes from each record will be considered?

- How can the severity of the diagnosis be captured?

- How many levels of severity will be acknowledged?

- What is the degree of confidence/certainty in the diagnosis?

- How will comorbidities be handled?

- What other data sources and code sets should be used (e.g., procedural codes, prescription data, lab values, etc?

Publicly available tools

There are several publically available models for those that prefer not to develop or maintain their own. These publicly available sources include, but are not limited to:

- National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS)

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW). (It does include several non-chronic or debilitating conditions as well).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Clinical Classification Software. (Developed through the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Hierarchical Condition Categories (CMS-HCCs)

- Health and Human Services (HHS) Hierarchical Condition Categories (HHS-HCCs)

Organizations that are increasingly taking on operational and financial risk in value-based care arrangements should consider the use of a commercially available model, often called “groupers” rather than relying simply on a clinical screening algorithm. There are numerous types of grouper models available on the market, all with a unique approach to handling the shortcomings of screening algorithms. A few well-known commercially available groupers include: Milliman MARA, Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Grouper (ACG), Optum’s Impact PRO, 3M Clinical Risk Groups (CRGs).

Step 2 Align: match resources and population needs

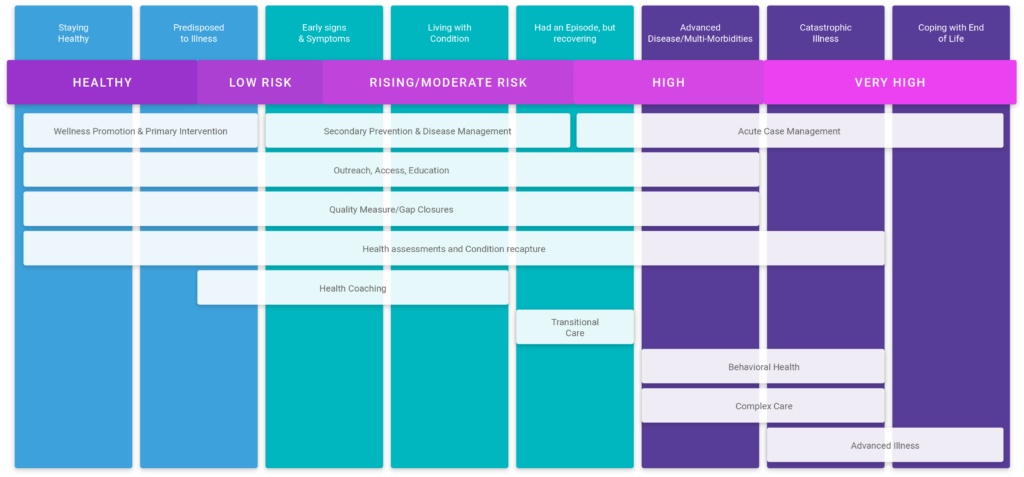

Now that we have the health journey mapped out and well defined (i.e., source data, source codes), the next step is to align the map to the appropriate service categories. Service categories are broadly classified into three groups: Wellness promotion & primary intervention; Secondary prevention & disease management; Acute case management.

- Wellness promotion and primary intervention: this level of care should focus on relationship building, education, access, and preventative care. Preventative care includes activities such as completing full health assessments during the annual wellness visit, keeping patients current on immunizations, as well as ordering/completing preventative screenings. Education should focus on behavioral and lifestyle factors as a way to prime patients for health coaching programs. Services at this level should be performed by clinical and administrative staff, with a focus on automating as much as possible.

- Secondary prevention & disease management: this level of care includes all of the activities involved with wellness promotion and primary intervention (e.g., access, education, access, and preventative care). However, it’s at this stage that specialized programs and targeted interventions should be established. Health coaching and transitional care are two great examples of targeted interventions deployed to support the rising risk population (“Early signs & symptoms”, “Living with a condition”, “Had an episode, but recovering”).

- Acute case management: this level of care is more resource-intensive, often requiring an additional step of panel management. Acute case management requires advanced skillset/licensing to treat, so managing health as far upstream along the health journey is important to controlling costs and addressing capacity concerns. This more personalized level of care should be reserved for the complex and advanced stages of illness (“Advanced disease/multi-morbidities”, “Catastrophic illness”, “Coping with the end of life”). These are the patients we would consider “High risk”. There are still components of wellness promotion and disease management services that can be applied, but in these cases, programs such as Complex care and Advanced illness would be most appropriate.

Step 3 Stratify: prioritize patients based on relative risk

One of the primary objectives in taking a patient-centered population-based approach to care delivery is keeping people as healthy as possible, for as long as possible in the most cost-effective way possible. Achieving this requires risk stratification.

Risk stratification is not a new term to healthcare, but it is a new concept to some. Risk stratification in its simplest form is a number. It’s a number that reflects the particular risk status of an individual relative to their peers (patients with similar comorbidities or resource needs). Risk status can be derived from many different factors, e.g., sex/age, vital health indicators, count and severity of illness/conditions, prior cost/utilization, lifestyle choices, etc. There are numerous solutions, both publicly and commercially available, for organizations looking to do this type of work.

Starting simple

A simple approach to identifying patients at greatest risk of developing ASCVD could be to use the ASCVD risk estimator screening tool. The ASCVD Risk Estimator is intended as a companion tool to the 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk and the 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults. This Risk Estimator enables health care providers and patients to estimate 10-year and lifetime risks for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), defined as coronary death or nonfatal myocardial infarction, or fatal or nonfatal stroke, based on the Pooled Cohort Equations and lifetime risk prediction tools.

Expanding the algorithm

Stratifying based on the ASCVD risk score alone would not be enough to maximize resources, nor would it be sufficient to stratify any person already diagnosed with ASCVD. To expand the model, we could take a similar approach to one that Sanford Health took in which they used factors across utilization, vital health indicators, screening tools, morbidity, and tobacco usage. This would be a good option for organizations that wanted to build their own risk stratification algorithm.

| Patient Age | 18-39, 0 pts

40-64, 1 pt 65+, 2 pts |

| Hospital Encounter in the past year | 1 pt for each admission in the past year – up to 3 pts |

| ED Encounter in the past year | 1 pt for each ED visit in the past year – up to 3 pts |

| No Show Office Visit | 1 pt for each no show office visit in the past year – up to 3 pts |

| A1C>/=9 | A1C 8 -8.9: 1 ptAIC >/9=2 pts |

| BP >/= 140/90 | BP >/= 140/90 – 1 pt |

| BMI > 40 | BMI >40, 2 ptsBMI</= 18.5, 2 pts |

| Last GAD 7, >9 | Last GAD score 10 -14, 1 pt

Last GAD >/= 15, 2 pts |

| Last PHQ 9 >9 | Last PHQ 9 score 10-14, 1 pt,

Last PHQ 9 score >/=15, 2 pts |

| ACT < 20 | ACT <20, 1 pt |

| Dx of COPD | Dx of COPD, 1pt |

| Dx of Diabetes | Dx of Diabetes, 1 |

| Dx of CHF | Dx of CHF, 1 pt |

| Dx of Chronic Liver Disease | Dx of Chronic Liver Disease, 1 pt |

| Dx of Depression | Dx of Depression, 1pt |

| Dx of CKD | Dx of CKD, 1 pt |

| Tobacco Use | Current smoker or null, 1 pt |

Advancing capabilities

Commercially available risk stratification algorithms offer much more advanced capabilities to identify patients that are at increased risk and who could benefit from targeted intervention. These solutions include Milliman’s MARA tool, Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Grouper (ACG) system, Optum’s Impact PRO, 3M Clinical Risk Groups (CRGs), plus many others.

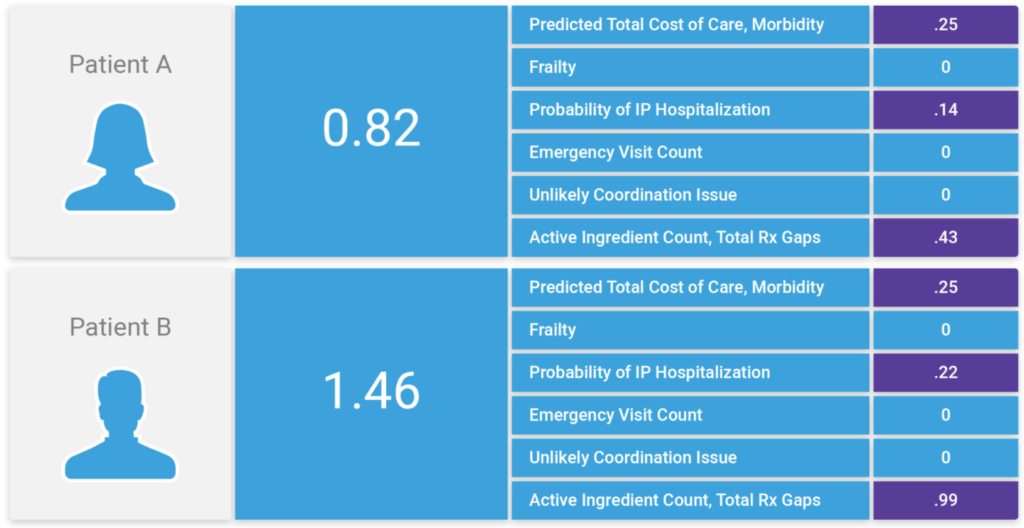

At Inflight Health, we’ve integrated the Johns Hopkins ACG system into the platform. This provides advanced stratification capabilities to consider predicted total costs and expected resource use, frailty, probability of IP hospitalization, emergency department utilization, potential coordination issues across specialties, pharmacy indicators, as well as Social Determinants of Health.

Using these factors as a baseline, we can then work with clinical teams to refine the algorithm and adjust the weighting for each, based on clinical intuition and organizational priorities. As patients are passed through these rules engines, they are ranked based on these factors, plus the overall ACG risk score. Over time, we are able to add new variables to the model and adjust weighting accordingly, so that we can dial in the algorithm to group patients by care/service needs and rank based on the severity of their overall health risk.

Parting thoughts

Achieving a patient-centered population-based approach to care management is a big undertaking, but it can be accomplished with small iterative and incremental steps over time. As we’ve illustrated throughout this post, it’s okay to start narrow and expand on capabilities; to focus initially on those populations that present with the greatest opportunity – as long as the end game is to deliver high-value coordinated care for every patient regardless of where they are at in their health journey.

Curious to learn more? Book a call with a member of our team or check out other resources.